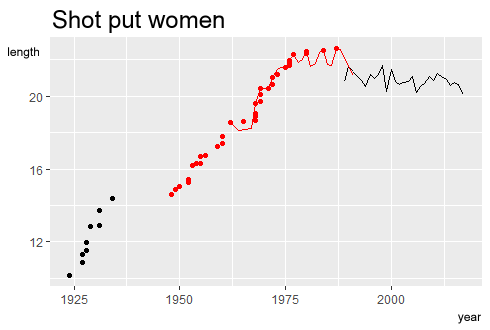

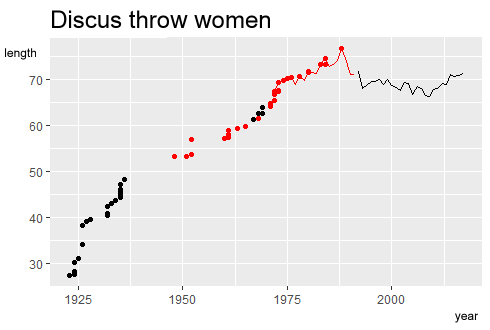

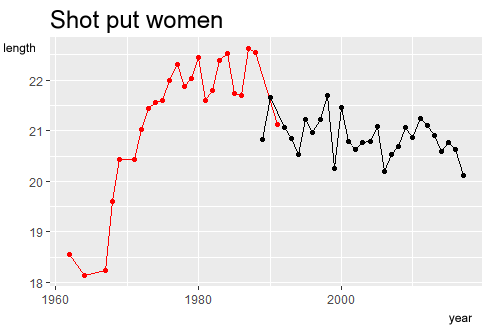

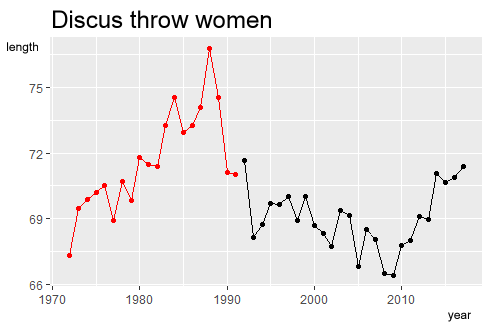

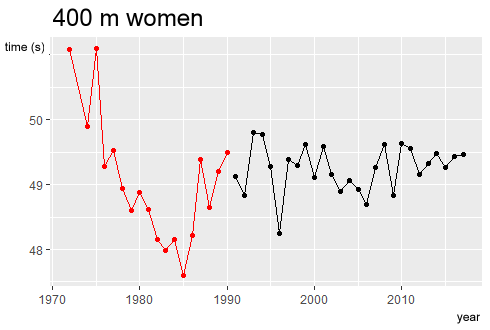

In the 1990s and in the following decade performances in shot put or discus throw not only show no improvement but gradually they even become slightly worse. It is predicted by East German scientists’ studies – in their opinion androgenic initiation, i.e. administration of male hormones to girls and women, has a permanent effect. After the initial increase in muscle strength and performance enhancement the values don’t return to pre-treatment levels after the drug is withdrawn. So, many female athletes in the 1990s and later still benefitted from the previous doping treatment.

“If you take anabolic steroids, then their long-term effect, besides the immediate increase in strength and dynamics, is the structural restoration of muscles,” says Czech sports doctor Jiří Dostal, explaining the effects of doping. “That means that new capillaries, mitochondrions and other structures are created leading to higher metabolic capacity unattainable by any hard training. They only need to be maintained when you are banned from competing and then you can return as ‘clean’ and start winning again.”

“But don’t think that you can simply start playing a sport and achieve better performances without any other effort,” says Dostal. “It’s not that easy. If an amateur cyclist takes EPO, his times don’t usually improve or they even become worse.”

“Doping won’t make anyone an Olympic winner,” continues Dostal. “But it can add the missing percentage to the performance that will move you up from third to first place. These athletes must always be highly trained individuals in whom the increase by a few percent means the difference between the absolute top and the top twenty. But it is very individual. A sportsman whose limitation is the use of oxygen in muscles and low aerobic capacity may stuff himself with EPO and have ‘marmalade’ instead of blood but it won’t help him anyway,” he adds.

Apart from an increase in performance, doping also helps athletes train much harder.

“An athlete famous for strenuous training is Jarmila Kratochvílová,” says a Czech TV article about the efforts of the Czech record holder in running. “She would sometimes run in a swimming pool, knee-deep in water with a gas mask on and wearing a vest with weights. She is said to have lifted 750 tonnes a year before the Moscow Olympics. She would lift a total of 16 tonnes per training session, she had to jump ten times with a 110kg barbell on her back and she could run three hundred meters eighteen times in a morning.”

Leaked Stasi documents

“One of the largest pharmacological experiments in history has been running for more than three decades,” says German Professor of molecular biology Werner Franke in his 1997 thesis Hormonal doping and androgenization of athletes: a secret program of the German Democratic Republic Government [Note: androgenisation is a change caused by male sex hormones]. “The administration of anabolic steroids was especially effective for androgenization in pubescent girls and young women.”

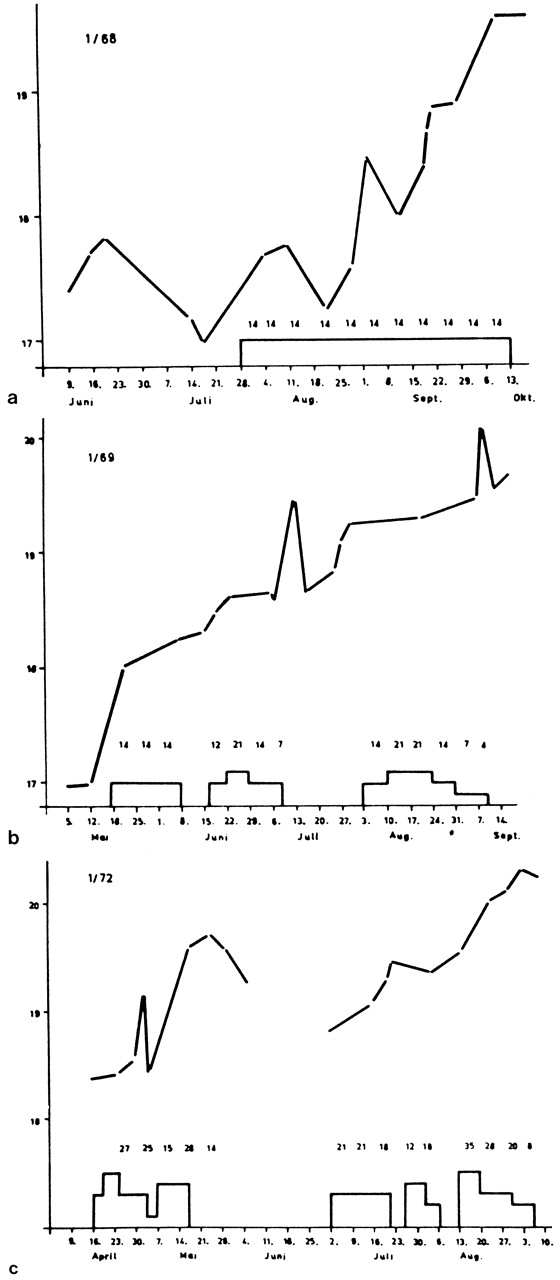

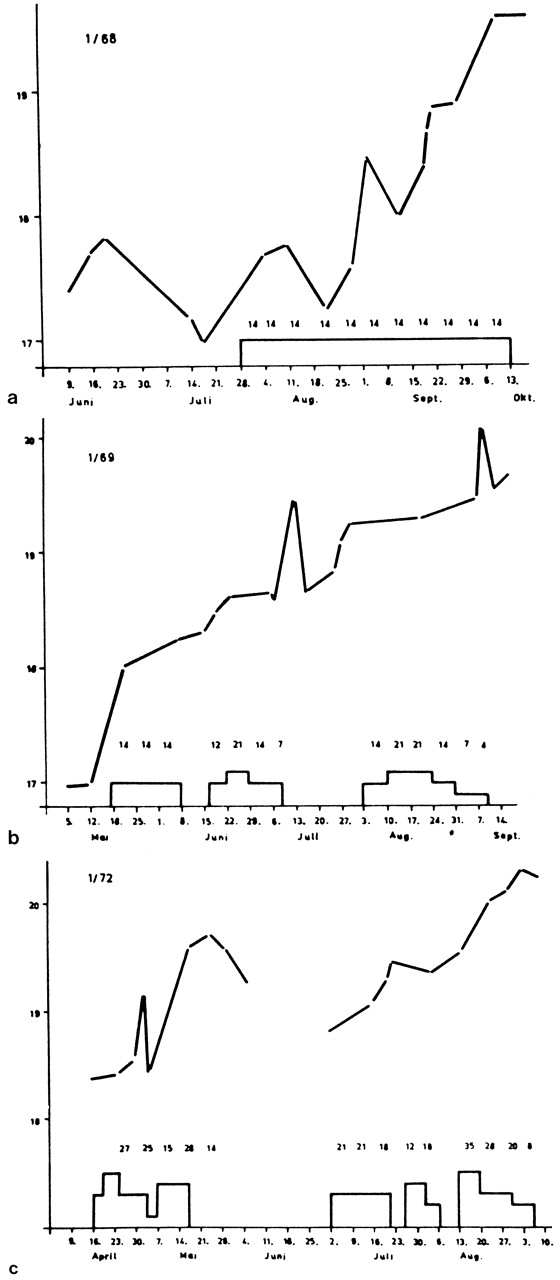

The influence of anabolic steroids on a shot-putter’s performance. The “y” axis shows the best performance in meters; the rectangles above the “x” axis mark the period of anabolics administration; the numbers mean the numbers of pills.

Source: W. Franke, B. Berendonk: Hormonal doping and androgenization of athletes

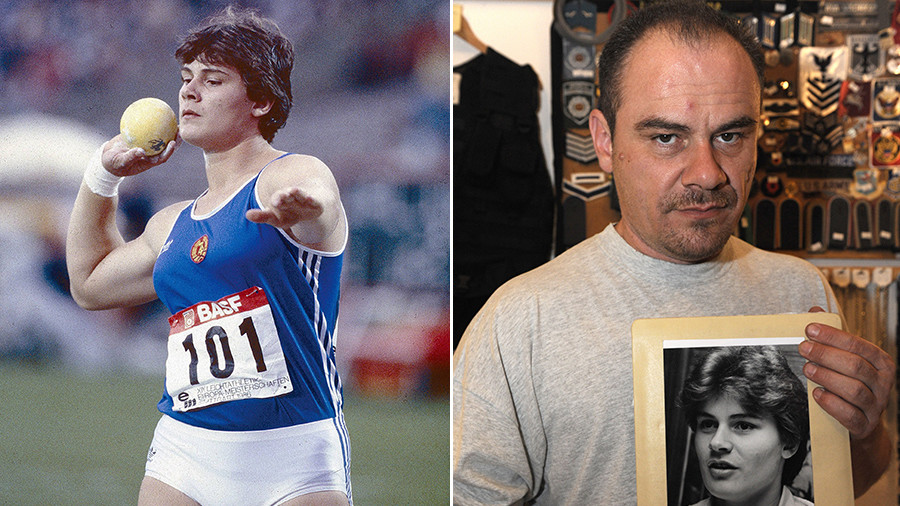

Doping is a personal topic for Franke. The thesis was co-authored by his wife, Brigitte Berendonk, a former top-level shot-putter and discus thrower, who emigrated from East Germany to the West. She had a lot of experience with doping and in 1991 she published a book called Doping: from Research to Deceit.

Franke’s study is based on the same materials. He uses more than 150 documents of the East German intelligence service, which the Stasi didn’t manage to destroy or which had leaked before the Communist regime fell. They include a lot of research studies that measure the impact of doping on performance; others describe undesirable side effects of the prohibited substances. Also fascinating are the case studies describing precisely the doping calendars and dosage of the substances for particular athletes.

“In the 1960s the German Democratic Republic was an obscure country dominated by the topic of the cold war and iron curtain,” says Franke. “The politicians thought that achievements in sports would be the fastest and cheapest way for the country with a population of seventeen million to gain international prestige.

They succeeded. In 1972 East Germans began to stand regularly on the winners’ podium along with the Americans and Russians. Their results were supposed to show the world that the Communist ideology was superior to the Western one.

According to Franke, more than two thousand athletes went through the doping programme every year.

The positive impact of anabolics on sports performances – at least according to the Stasi records of that time – sound almost unbelievable:

- Shot put, men: 2.5–4m

- Shot put, women: 4.5–5m

- Discus throw, men: 10–12m

- Discus throw, women: 11–20m

- Hammer throw: 6–10m

- Javelin, women: 8–15m

- 400 metres, women: 4–5s

- 800 metres, women: 5–10s

- 1,500 metres, women: 7–10s

However, in 1977 the regime faltered for the first time: shot-putter Ilona Slupianek had a positive doping test. In order to prevent that from happening again East Germany introduced its own doping controls. Their purpose was not to limit doping – the testing of athletes before the official tests was to ensure that nobody with problematic values would compete in the sports events. Those who didn’t pass stayed at home due to “an injury” or “being out of shape suddenly.” The measure proved successful – Slupianek was the last East German top female athlete to be revealed. Later on, the same methods began to be used by other Eastern Bloc countries, including Czechoslovakia.

While the athletes passed doping tests out of their country without being suspected, in East Germany systematic doping was an open secret. The prohibited substances for the top athletes were procured by state coaches and national teams’ doctors; the “bush league” had to rely on black market. Many athletes “downed” the substances without being checked by doctors, so they endangered their health much more. According to Franke, black-market synthetic anabolics, such as oral-turinabol, were available to nine- or twelve-year-old children.

The stimulus of the black market was the rewards for the athletes and their coaches. For increasing the GDR’s international prestige they would be given financial rewards or permissions to travel to the West.

By the end of the 1980s doping had become so obvious that international sports institutions including the Olympic Committee couldn’t ignore it. The last straw was the 100-metre dash at the Seoul Olympics in 1988. Canadian Ben Johnson’s positive doping test meant the end even for the state-controlled doping in East Germany. By the way, in the following years other five out of seven sprinters in the same race had positive tests.

Anabolics for nine-year-old girls

At the beginning of the 1970s anabolics were nothing unusual among top athletes and it wasn’t until 1976 that they were banned. According to Franke they were normally used by U.S. athletes. However, the East German trainers were the first to administer them to women on a large scale.

They also drastically increased dosage, which became obvious at the end of the 1970s. When an American athlete at the Montreal Olympics, where the East German swimmers won 11 out of the 13 medals, asked about their unnaturally low-pitched voices, their trainer replied: “We have come here to swim, not sing.”

“The androgenisation of girls and young women was the most effective part of the doping programme,” says Franke. “The doses were surprisingly high. Many top female athletes and swimmers were given higher amounts of anabolics than men in the same disciplines.”

One of the measures that were to prevent positive doping tests after Slupianek’s doping exposure was the steroid therapy. Trainers and doctors knew exactly how long before a sporting event to discontinue the use of anabolic steroids so that they left no traces. At the same time they were looking for ways to dope athletes before as well as during the event. The result was the use of testosterone injections, which the tests could not reveal. Therefore, complicated doping protocols began to be created, working with the “bridging” of the period when athletes didn’t take the main training anabolics.

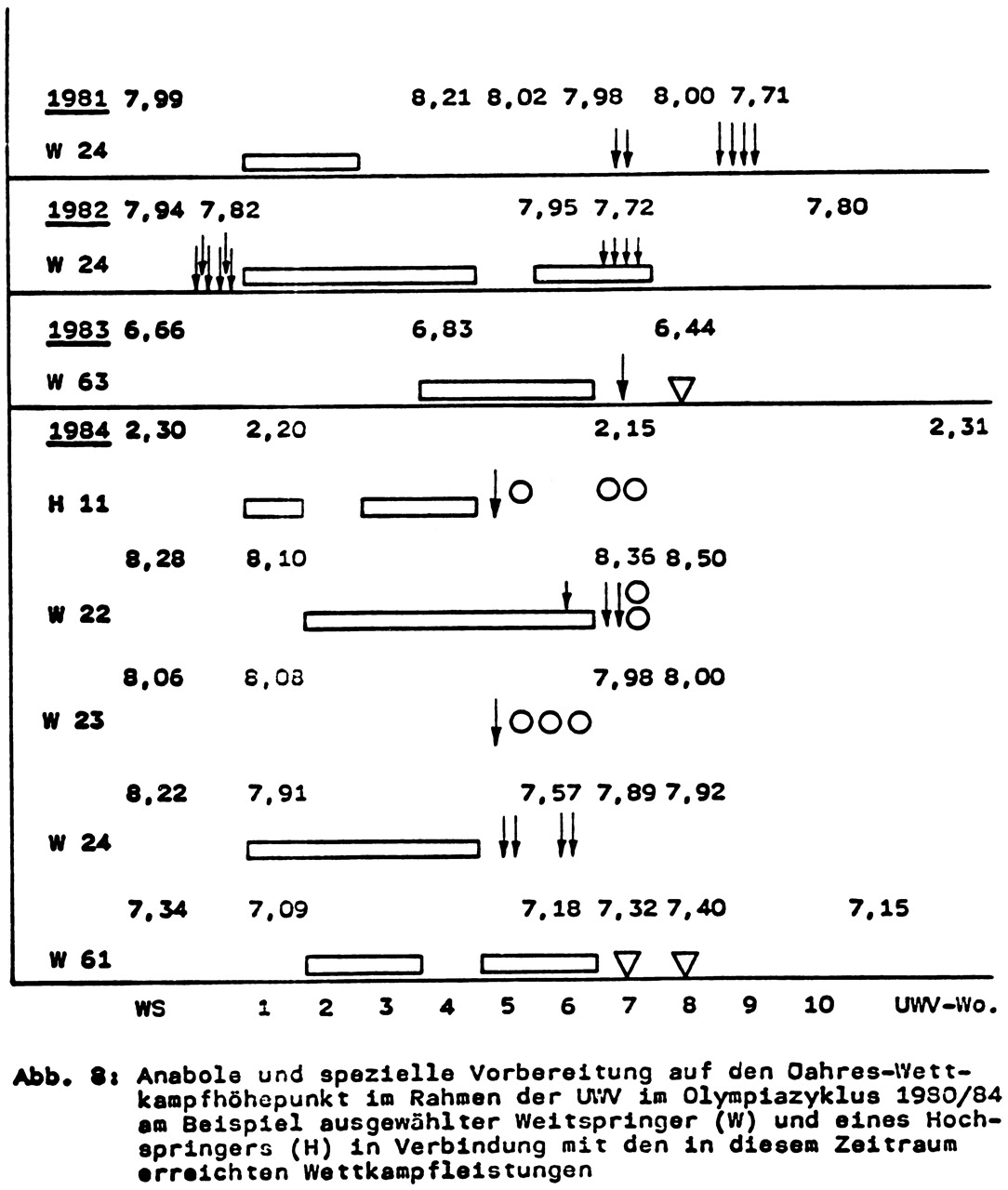

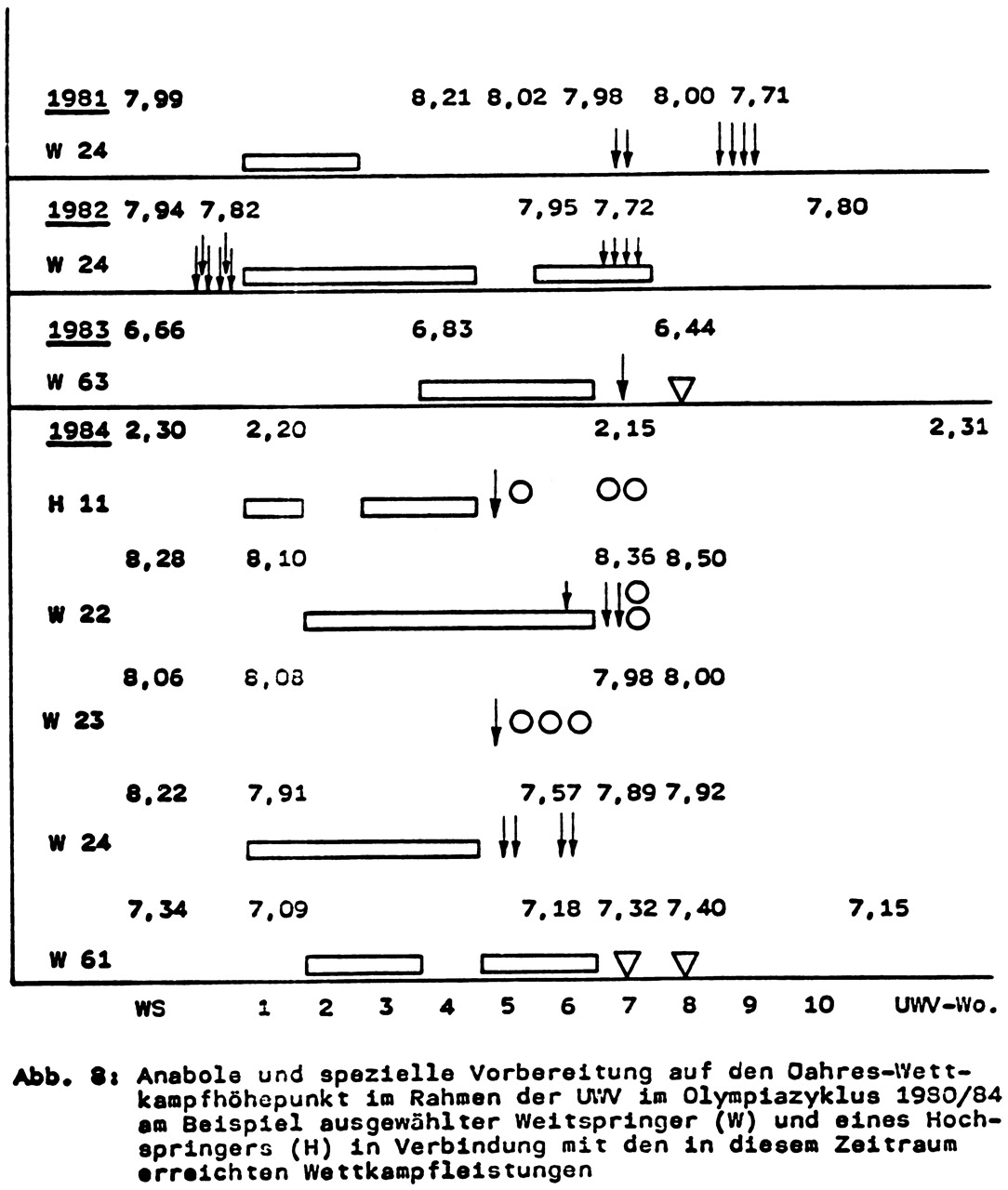

Illustration of steroid bridging from the Stasi documents: the sheet shows six athletes’ doping schemes ten weeks before a sporting event; the rectangles mark the application of anabolic steroids, such as Oral-Turinabol; the arrows, triangles and circles mark the application of testosterone.

Source: W. Franke, B. Berendonk: Hormonal doping and androgenization of athletes

In order to check the level of testosterone, doping tests measured the ratio between testosterone and the related epitestosterone (T:E), which doesn’t influence performance. The levels of both hormones are normally approximately identical. A distinctly higher level of testosterone means doping.

The East German scientists coped with the test quite easily: apart from testosterone they also learned to increase the level of epitestosterone, so the T:E ratio remained stable. That enabled them to administer much higher doses to the female athletes. They were so high that in 1984 the second highest-ranking man of the doping programme, Manfred Höppner, started to wonder whether the experiment hadn’t gone too far.

“[This athlete] was among the selected top athletes who were prepared for their competitions at the Olympic Winter Games with considerable amounts of testosterone and simultaneous counterinjections of epitestosterone,“ says Höppner in one of the documents that the Stasi didn’t manage to destroy. „Similar supporting measures were also performed [for her] at the subsequent World championships. …[her] extraordinarily positive results… will be unique and not reproducible, also not in her own best interest, as already now her facial features have virilized and her voice has changed,“ warns Höppner.

According to Franke this extraordinarily dangerous procedure with high doses of both substances began to be used in 1983, mostly for swimmers and rowers.

Besides a low-pitched voice, increased growth of bodily hair or “anabolic acne” the results included an extreme disturbances in libido, serious liver and kidney dysfunctions, malformations of the foetus in pregnancy or abortions ordered by the trainers. Getting out of the training programme was not easy.

“[Despite Höppner’s concerns] androgenic treatments of other girls continued,” says Franke in his study. “One year later one of them noticed the same and other virilising side effects, including a deepened voice, but she was not allowed to stop taking the medication. She consequently decided to defect from the GDR to the West… She was the first to report the truth about the systematic and forceful androgenisation of young athletes… As evidence she brought her “vitamin pills”, which were identified in a West German laboratory as Oral-Turinabol.” [Note: East German doctors described the drugs as vitamin B12 to the athletes who took them].

“Although her report was widely publicized,” adds Franke, “the sports authorities of the world, including the IOC, remained silent, a reaction that pleased the GDR officials.”

According to the WADA data and according to oral reports, doping is most widely used in cycling. In 2004 almost 5% of tested cyclists failed the test but since then the number has significantly decreased. However, strong opinions expressed by former racers or cyclists caught doping suggest that the real percentage of cyclists using prohibited substances is much higher.

“Professional cycling is organized crime,” American cyclist Floyd Landis, who had to return his gold medal from the most difficult race, Tour de France, because of a positive test, said to the USA Today in February 2013.

It was in the same year that the seven-time winner of the Tour de France, Lance Armstrong, also admitted doping.

“Was it humanly possible to win the Tour de France without doping, seven times?” asked TV host Oprah Winfrey the cyclist after he had returned all his medals. “Not in my opinion,” replied Armstrong.

“He took what we all took: EPO, testosterone, a blood transfusion,” wrote Armstrong’s former teammate Tyler Hamilton after the discovery. He was the one who started talking about Armstrong’s doping publicly and made him confess.

Most recently, British cyclist Chris Froome, the winner of the last three years of Tour de France, has been facing suspicion of doping. At last year’s Vuelta (Tour of Spain) twice the allowed dose of Salbutamol was found in his sample. Froome defends himself by saying that it is a medication against asthma, which he suffers from. However, Salbutamol is a prohibited substance because it can enhance performance.

Froome is not the only one to suffer from asthma. “The rain on the final stages of the Vuelta cleared the air and it wasn’t necessary to use the medicine,” another asthmatic, Vincenzo Nibali, who came second, criticised him.

“It is interesting that while at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles exercise-induced asthma was stated by 10% athletes, at the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer it was 60%,” says clinical biochemist Libor Vítek from the First Medical School of the Charles University on his website. “The reason is probably the legalization of the use of these substances if the athletes are officially regarded as asthmatics.”

“The Tour de France used to be called the Tour de Pharmacy and it wasn’t far from the truth. I am convinced that top-level cycling is much cleaner now,” says sports doctor Jiří Dostal in defence of professional cycling. “The UCI World Tour teams are extremely careful not to be involved in doping systematically because they would immediately lose their sponsors and it would destroy them. If an athlete’s doping is proved, the team usually dissociate themselves from him. The current case of Chris Froom might be the only exception.”

Doping controls can be outsmarted easily

The WADA data published by The Guardian show a high percentage of positive findings among weightlifters, too. That is not surprising since anabolics have always been popular performance enhancing substances in weightlifting.

Surprisingly, there is a relatively high percentage of positive tests in basketball and baseball. Since 2005 the American Major League Baseball has been facing many serious cases of the use of anabolic steroids and the growth hormone. They were investigated by the American Congress, whose final Mitchell Report in 2007 revealed about eighty doping sportsmen.

“In the USA there is a strong anti-doping agency, the USADA, so state-controlled doping like in Russia or China is unthinkable,” points out Jiří Dostal. “On the other hand, there have been many U.S. cases involving commercial distributors and laboratories. One of them is the BALCO case, in which a laboratory supplied anabolics to many sportsmen, including baseball players. The cycling cases of the 1990s and of the turn of the century are similar: the Festina doping scandal or Operación Puerto in Spain.”

The WADA statistics don’t include bodybuilding. It is almost certainly the most doping-infested sport. The vast majority of sportsmen with positive tests on the Czech Anti-Doping Committee website are bodybuilders and international statistics show similar results. Furthermore, the scope of the revealed substances used by bodybuilders shows that they put their health at risk to a significantly higher degree than other athletes. For instance, Jiří Lasík’s two-year-old doping record lists twelve prohibited substances, mostly anabolic steroids. Similar records are quite common among bodybuilders.

However, doping controls have a crucial weakness, which athletes have been able to take advantage of since the 1980s. The tests measure quite accurately the content of prohibited substances in the body but they go only a few days or weeks, at the most, back. Therefore, the use of some kinds of doping, such as anabolics, can simply be discontinued only a few weeks before the race. They have already played their role in training and in the growth of the athlete’s muscles, so now he/she may be “clean” during the race.

Or, as the “training” plan of the East German athletes shows, the use of easily detectable doping is discontinued before the tournament and substances that can be masked more easily are used for “bridging the gap.”

Therefore, since 1989 anti-doping commissioners have been testing athletes between races. Unexpected checks mean a higher risk of being caught doping but they only focus on top athletes.

As a result, rather than showing the real extent of doping, positive doping controls only reveal those athletes who are “unlucky.”

Forget the controls – drugs are taken by tens of percent

One of the few detailed studies on doping, published in Deutsche Zeitschrift für Sportmedizin in October 2016, suggests much higher numbers.

“The number of positive anti-doping tests has remained consistently low in the past 30 years, at approximately 2%,” say the authors. “However, given the exposure of structural doping practices and the involvement of anti-doping laboratories (e.g. in Russia), we can suggest that the high prevalence of doping… is more realistic than the low number of positive doping cases.”

The study collected data on the doping cases of top athletes in 2000–2013. Until then there had been no overall statistics for athletes with positive tests. The WADA only began to publish them later. So, the authors collected data from national anti-doping agencies, verifying them and completing them with information from the media.

They collected 1,236 doping cases. The largest percentage (over 10%) occurred in Russia, followed quite closely by the United States, Italy, Spain and Germany. Almost one third of the cases concerned track and field athletes, followed by weightlifters and cyclists.

The study also focused on the types of performance enhancing substances. In almost 40% of the cases they were anabolic steroids. Moreover, the authors infer that another 10% of cases, in which the substance isn’t known, involved anabolics. Another 16% of cases involved blood doping and 14% the use of stimulants, usually amphetamine, ephedrine or cocaine, just before the race.

In the Olympic years there was twice as much doping (four times as much among Russian athletes) as in the periods between the Olympic Games.

The data showed an interesting finding about whether it is men or women who dope more. In the case of the Russians it was women (58%, and among track and field athletes 74%), while in the case of the Spaniards and Italians men predominated distinctly.

“The difference can be partially explained by the fact that in the Olympics the Russians are mainly represented by women, which can be the result of some sociocultural factors,” says the study. “Similarly, the predominance of male doping in Italy and Spain can be explained by the popularity of cycling in those countries.”

“The reason could also be that women are more sensitive to doping,” adds Jiří Dostal. “We can say that women don’t reach their metabolic maximum and doping actually helps them to achieve the level of men’s performances. But in men it’s a complex matter and it is much more difficult to achieve the effect.”

One of the studies on which the researchers rely says there are between 26% and 48% of doping athletes. This two-year-old study collects data from German athletes by means of an anonymous web questionnaire.

“It is surprising that sportspeople, trainers, officials, politicians and other people involved in professional sports do not take notice of the large-scale doping although the data shows that 4.2–35% of athletes take drugs and in track and field in some countries it is over 50%,” the authors of the study conclude.

Cross-country skiing scandal a week before the Pyeongchang Olympics

The last doping case happened less than a week before the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Pyeongchang. The German ARD television along with the British newspaper The Sunday Times carried out an analysis of the blood samples of two thousand cross-country skiers from 2001–2010. According to them, the data, which they had obtained from an anonymous source, prove widespread doping among cross-country skiers.

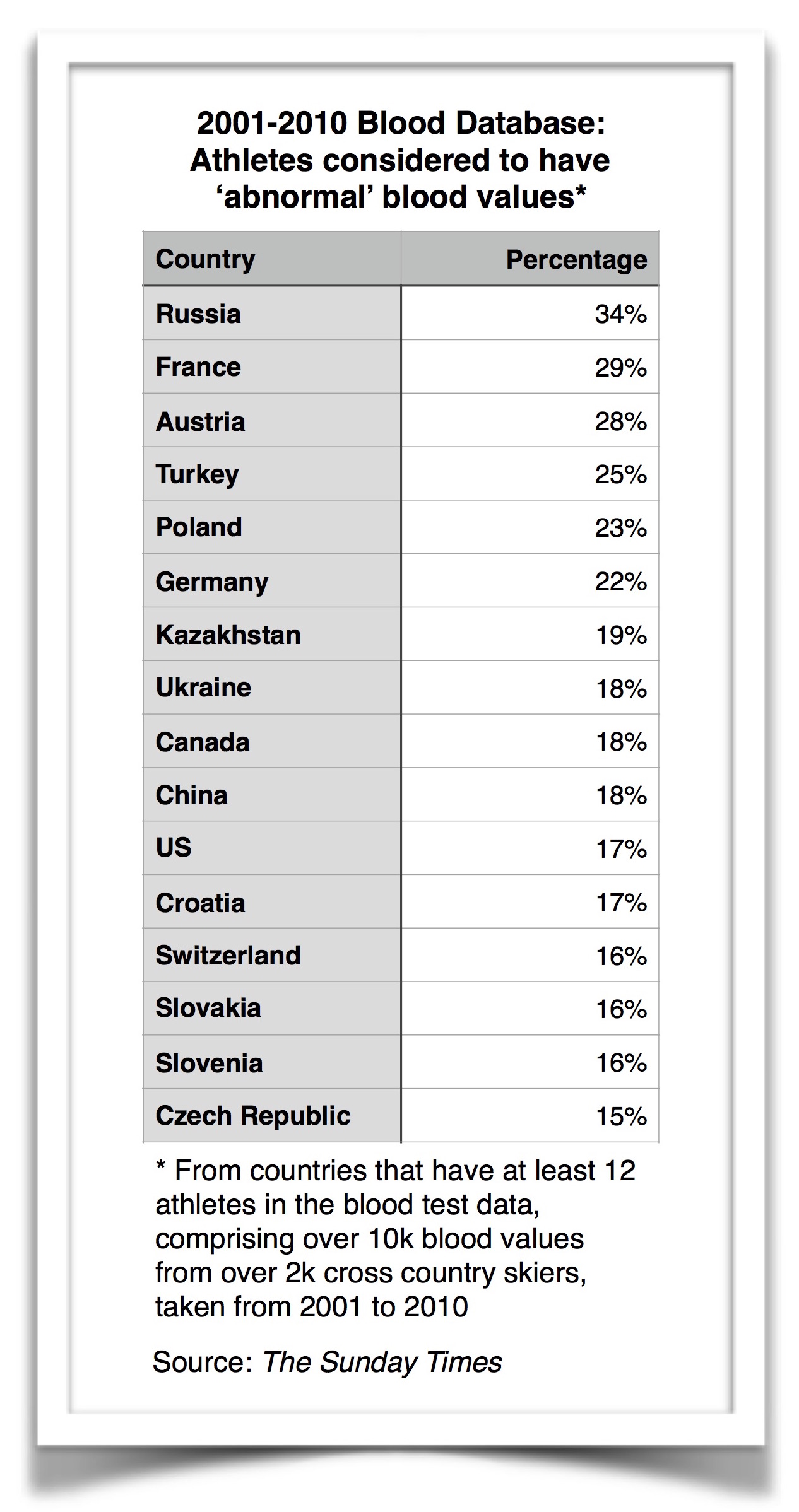

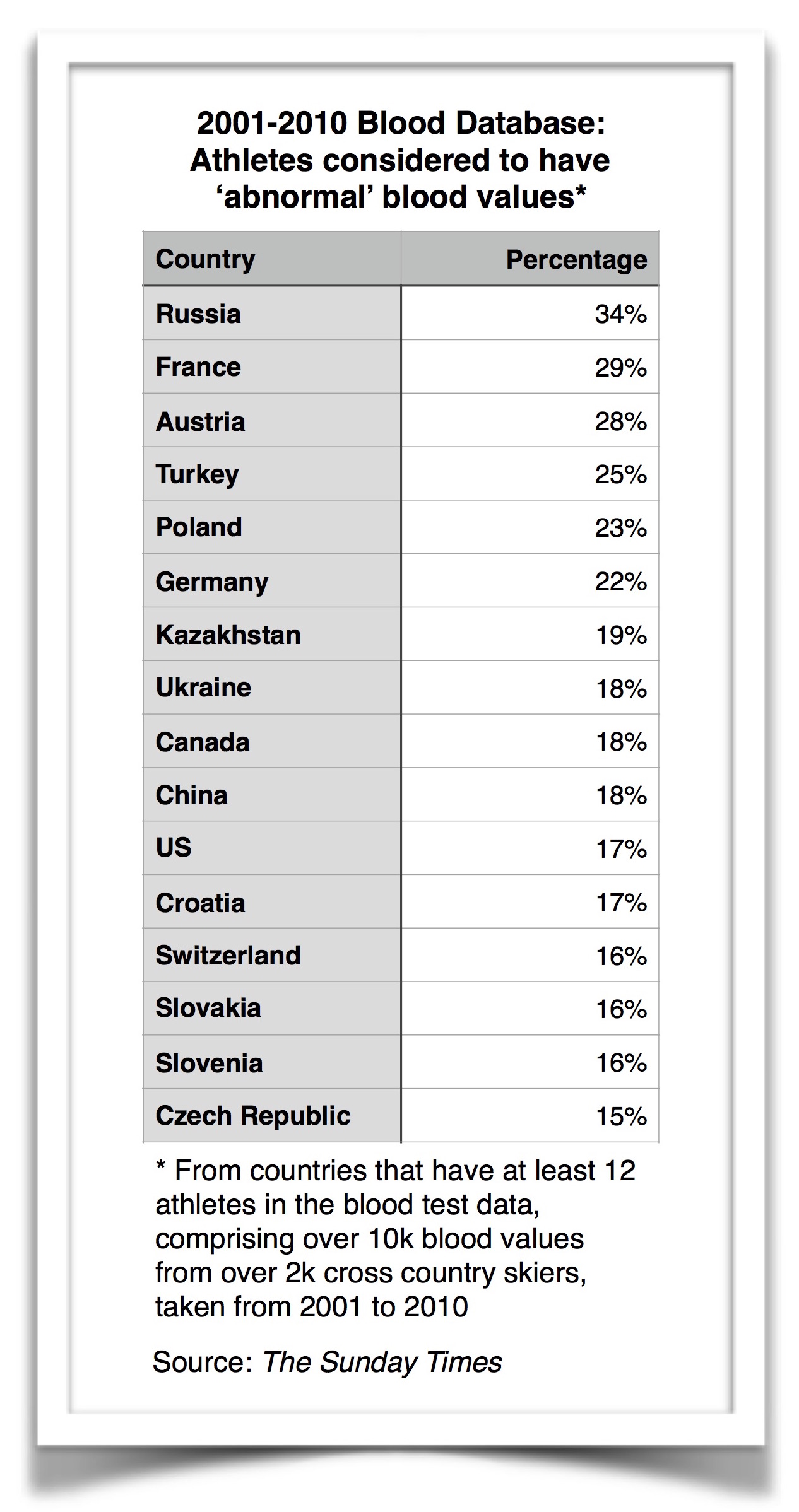

Percentage of cross-country skiers with suspicious blood tests.

Source: The Sunday Times

“A third of the Olympic and world championship medals in those years, including 91 gold ones, were won by skiers with blood tests classed as “likely doping” or “suspicious,” says the Sunday Times. According to it, fifty cross-country skiers competing in the Olympics in Korea show abnormal results in the tests, too.

“Russia again emerges as the world leader in the winter sports cheating table,” continues The Sunday Times. “More than 76% of cross-country skiing medals awarded to the country were won by skiers with abnormal blood-test results.”

Those suspected of doping include a lot of top-level athletes from Norway, Germany, Sweden, Italy and other countries that traditionally do well in winter sports.

The journalists do not give the names of the skiers because blood tests cannot decidedly prove that athletes use doping. According to the doctors cooperating with the newspaper, each sample has less than a one in 100 chance of the levels being natural.

The International Ski Federation (FIS) refused to comment on the findings of the British saying that these were mere suspicions. According to the WADA rules doping cannot be deduced from a single blood sample, as the addressed doctors did. According to the WADA, even for a suspicion it is necessary to monitor samples for a longer period of time and even then it takes a lot of effort to prove doping. The results are repeatedly examined by anti-doping laboratories and only if the athlete cannot defend themselves before the commission, it is considered to be a doping finding.

The Sunday Times also published a ranking of countries according to the percentage of suspicious blood tests – in 24 countries, including the Czech Republic, more than 10% of the samples show abnormal values. The first are the Russians but the French, Austrians and Germans also show high numbers.

Absolution

If doping is so omnipresent, why not allow it?

“Because it brings inequality to sports and sometimes endangers health,” says sports doctor Jiří Dostal. ”Because some parents and countries have no scruples about doping children. Because the numbers of the dead and disabled would sky-rocket,” he adds.

“There are, perhaps, logical arguments in favour of lifting the ban on doping,“ The Guardian sums up. “It wouldn’t be ‘unfair,’ as every athlete has access to the same drugs, so it levels the playing field. It could even make it more inclusive: people normally get to be top athletes because of ‘unfair’ genetic advantages, so those who normally couldn’t keep up can use drugs to compensate and stay competitive. And, potentially, it could make the games far more interesting. World records constantly being smashed, athletes being faster, stronger, more enduring. What’s not to like?”

The Guardian gives its own reply to this rhetorical question.

“How people respond to drugs is heavily influenced by their own physiology and genes… so it would still be something of a genetic lottery… Making doping compulsory would only drastically increase the risk of serious damage to the health of an athlete. And it would be compulsory… [It] would make the playing field even more uneven, not less. Countries like the US and China would have the resources and infrastructure to obtain the best performance enhancers for their athletes and maximise their safety when using them.”

The last argument is not just theory. There are speculations about countries like China working on managing genetic doping.

“We know that it is possible to insert information about higher production of red blood cells into DNA. The effect would be similar to that of EPO,” says Dostal in a two-part interview about doping. “The ACTN3 gene increases glycolytic capacity and if we could insert it into a sprinter’s muscle cells, such a sprinter couldn’t be beaten even by Usain Bolt.”

“One of the problems of doping is that it has become a political matter,” continues Dostal. “Like it or not, doping has become a tool in the fight between world powers. An example is the punishment of Russian athletes and the counteraction of Russian hackers who published secret documents about many Western athletes’ biological passports.”

“But it’s obvious that the Russian, Kenyan or, for instance, Brazilian laboratories were one big cheat masking and sometimes even managing the doping controls so that the athletes were clean,“ he adds. “In fact, they didn’t do anything else than East Germany in the 1980s. I have no illusions about the Western athletes being clean. But I don’t think that Western countries, with their high degree of control and certification, would be capable of doing something like that.”

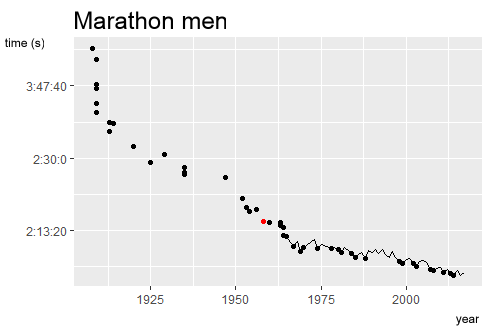

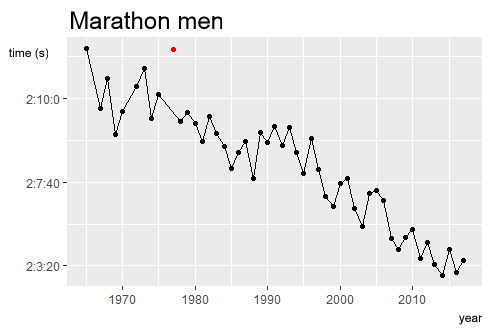

“My informed guess is that there is less doping nowadays,” sums up Dostal. “Professional sport is cleaner than before. You only need to look at the development of world records years ago and now. Look at the times and performances achieved now and ten years ago. On the other hand, doping is incredibly rampant at the amateur level, where it’s not checked. That’s certainly alarming.”

Jan Boček, Jan Cibulka a Markéta Adamcová